Alexander Jannaeus

| Alexander Jannaeus | |

|---|---|

| King and High Priest of Judaea | |

Portrait from Promptuarium Iconum Insigniorum (1553) by Guillaume Rouillé | |

| King of Judaea | |

| Reign | c. 103 – c. 76 BCE |

| Predecessor | Aristobulus I |

| Successor | Salome Alexandra |

| High Priest of Judaea | |

| Predecessor | Aristobulus I |

| Successor | Hyrcanus II |

| Born | c. 127 BCE |

| Died | c. 76 BCE Ragaba |

| Spouse | Salome Alexandra |

| Issue | Hyrcanus II Aristobulus II |

| Dynasty | Hasmonean |

| Father | John Hyrcanus |

| Religion | Hellenistic Judaism |

Alexander Jannaeus (Ancient Greek: Ἀλέξανδρος Ἰανναῖος Aléxandros Iannaîos;[1] Hebrew: יַנַּאי Yannaʾy;[2] born Jonathan יהונתן) was the second king of the Hasmonean dynasty, who ruled over an expanding kingdom of Judaea from 103 to 76 BCE. A son of John Hyrcanus, he inherited the throne from his brother Aristobulus I, and married his brother's widow, Queen Salome Alexandra. From his conquests to expand the kingdom to a bloody civil war, Alexander's reign has been described as cruel and oppressive with never-ending conflict.[3] The major historical sources of Alexander's life are Josephus's Antiquities of the Jews and The Jewish War.[4]

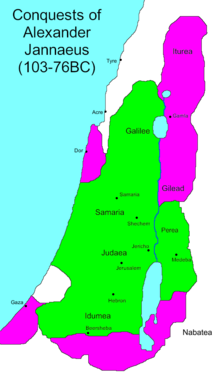

The kingdom reached its greatest territorial extent under Alexander Jannaeus, incorporating most of Palestine's Mediterranean coastline and regions surrounding the Jordan River. Alexander also had many of his subjects killed for their disapproval of his handling of state affairs. Due to his territorial expansion and adverse interactions with his subjects, he was continuously embroiled with foreign wars and domestic turmoil.[5]

Family

[edit]Alexander Jannaeus was the third son of John Hyrcanus by his second wife. When Aristobulus I, Hyrcanus' son by his first wife, became king, he deemed it necessary for his own security to imprison his half-brother. Aristobulus died after a reign of one year. Upon his death, his widow, Salome Alexandra had Alexander and his brothers released from prison. One of these brothers is said to have unsuccessfully sought the throne.

Alexander, as the oldest living brother, had the right not only to the throne, but also to Salome, the widow of his deceased brother, who had died childless. Although she was thirteen years older than him, he married her in accordance with the Jewish law of levirate marriage. By her he had two sons: the eldest, Hyrcanus II, became high priest in 62 BCE; and Aristobulus II, who was high priest from 66 – 62 BCE and started a bloody civil war with his brother, ending in his capture by Pompey the Great.

Like his brother, Alexander was an avid supporter of the aristocratic priestly faction known as the Sadducees. His wife Salome came from a Pharisaic family. Her brother was Simeon ben Shetach, a famous Pharisee leader. Salome was more sympathetic to their cause, and protected them throughout his turbulent reign.

Like his father, Alexander served as high priest. This raised the ire of the Pharisees, who insisted that these two offices should not be combined. According to the Talmud, Alexander was a questionable desecrated priest, rumour had it that his mother was captured in Modi'in and violated, and, in the opinion of the Pharisees, was not allowed to serve in the temple. This infuriated the king and he sided with the Sadducees who defended him. This incident led the king to turn against the Pharisees, and he persecuted them until his death.[6]

War with Ptolemy Lathyrus

[edit]Alexander's first expedition was against the city of Ptolemais. While Alexander went ahead to besiege the city, Zoilus of Dora took the opportunity to see if he could relieve Ptolemais in hopes of establishing his rule over coastal territories. Alexander's Hasmonean army quickly defeated Zoilus's forces. Ptolemais then requested aid from Ptolemy IX Lathyros, who had been banished by his mother Cleopatra III. Ptolemy had founded a kingdom in Cyprus after being cast out by his mother.[7]

The situation at Ptolemais was seized as an opportunity by Ptolemy to possibly gain a stronghold and control the Judean coast in order to invade Egypt by sea. An individual named Demaenetus convinced the inhabitants of their imprudence in requesting Ptolemy's assistance. They realised that by allying themselves with Ptolemy, they had unintentionally declared war on Cleopatra. When Ptolemy arrived at the city, the inhabitants denied him access.[7]

Alexander too didn't want to be involved in a war between Cleopatra and Ptolemy, so he abandoned his campaign against Ptolemais and returned to Jerusalem. After offering Ptolemy four hundred talents and a peace treaty in return for Zoilus's death, Alexander met him with treachery by negotiating an alliance with Cleopatra. Once he had formed an alliance with Ptolemy, Alexander continued his conquests by capturing the coastal cities of Dora and Straton's Tower.[8]

As soon as Ptolemy learned of Alexander's scheme, he was determined to kill him. Ptolemy put Ptolemais under siege, but left his generals to attack the city, while he continued to pursue Alexander. Ptolemy's pursuit caused much destruction in the Galilee region. Here he captured Asochis on the Sabbath, taking ten thousand people as prisoners. Ptolemy also initiated an unsuccessful attack on Sepphoris.[8]

Battle of Asophon

[edit]Ptolemy and Alexander engaged in battle at Asophon near the Jordan River. Estimated to have fifty to eighty thousand soldiers, Alexander's army consisted of both Jews and pagans. At the head of his armed forces were his elite pagan mercenaries. They were specialised in Greek-style phalanx. One of Ptolemy's commanders, Philostephanus, began the first attack by crossing the river that divided both forces.[9]

The Hasmoneans had the advantage. Philostephanus held back a certain amount of his forces whom he sent to recover lost ground. Perceiving them as vast reinforcements, Alexander's army fled. Some of his retreating forces tried to push back, but quickly dispersed as Ptolemy's forces pursued Alexander's fleeing army. Thirty to fifty thousand Hasmonean soldiers died.[9]

Ptolemy's forces at Ptolemais succeeded in capturing the city. He then continued to conquer much of the Hasmonean kingdom, occupying the entirety of northern Judea, the coast, and territories east of the Jordan River. While doing so, he pillaged villages and ordered his soldiers to cannibalise women and children to create psychological fear towards his enemies. At the time, Salome Alexandra was notified of Cleopatra's approach to Judea.[10]

Intervention of Cleopatra III

[edit]Realising that her son had amassed a formidable force in Judea, Cleopatra appointed Jewish generals Ananias and Chelkias to command her forces. She went with a fleet towards Judea. When Cleopatra arrived at Ptolemais, the people refused her entry, so she besieged the city. Ptolemy, believing Syria was defenseless, withdrew to Cyprus after his miscalculation. While in pursuit of Ptolemy, Chelkias died in Coele-Syria.[11]

The war abruptly came to an end with Ptolemy fleeing to Cyprus. Alexander then approached Cleopatra. Bowing before her, he requested to retain his rule. Cleopatra was urged by her subordinates to annex Judea. Ananias demanded she consider the residential Egyptian Jews who were the main support of her throne. This induced Cleopatra to modify her longings for Judea. Alexander met her demands and suspended his campaigns. These negotiations took place at Scythopolis. Cleopatra died five years later. Confident, after her death, Alexander found himself free to continue with new campaigns.[12]

Transjordan and coastal conquest

[edit]

Alexander captured Gadara and fought to capture the strong fortress of Amathus in the Transjordan region, but was defeated.[13] He was more successful in his expedition against the coastal cities, capturing Raphia and Anthedon. In 96 BCE, Jannaeus defeated the inhabitants of Gaza. This victory gained Judean control over the Mediterranean outlet of the main Nabataean trade route.[14] Alexander initially returned his focus back to the Transjordan region where, avenging his previous defeat, he destroyed Amathus.[15]

Battle of Gaza

[edit]Determined to proceed with future campaigns despite his initial defeat at Amathus, Alexander set his focus on Gaza. A victory against the city wasn't so easily achieved. Gaza's general Apollodotus strategically employed a night attack against the Hasmonean army. With a force of two thousand less-skilled soldiers and ten thousand slaves, Gaza's military was able to deceive the Hasmonean army into believing they were being attacked by Ptolemy. The Gazans killed many and the Hasmonean army fled the battle. When morning exposed the delusive tactic, Alexander continued his assault but lost a thousand additional soldiers.[16]

The Gazans remained defiant in hopes that the Nabataean kingdom would come to their aid. The city eventually suffered defeat due to its own leadership. Gaza at the time was governed by two brothers, Lysimachus and Apollodotus. Lysimachus convinced the people to surrender, and Alexander peacefully entered the city. Though he at first seemed peaceful, Alexander suddenly turned against the inhabitants. Some men killed their wives and children out of desperation, to ensure they wouldn't be captured and enslaved. Others burned down their homes to prevent the soldiers from plundering. The town council and five hundred civilians took refuge at the Temple of Apollo, where Alexander had them massacred.[16]

Judean Civil War

[edit]War with Obodas I

[edit]The Judean Civil War initially began after the conquest of Gaza around 99 BCE. Due to Jannaeus's victory at Gaza, the Nabataean kingdom no longer had direct access to the Mediterranean Sea. Alexander soon captured Gadara, which together with the loss of Gaza caused the Nabataeans to lose their main trade routes leading to Rome and Damascus. After losing Gadara, the Nabataean king Obodas I launched an attack against Alexander in a steep valley at Gadara, where Alexander barely managed to escape. After his defeat in the Battle of Gadara, Jannaeus returned to Jerusalem, and was met with fierce Jewish opposition.[17]

Feast of Tabernacles

[edit]During the Jewish holiday Sukkot, Alexander Jannaeus, while officiating as the High Priest at the Temple in Jerusalem, demonstrated his displeasure against the Pharisees by refusing to perform the water libation ceremony properly: instead of pouring it on the altar, he poured it on his feet. The crowd responded with shock at his mockery and showed their displeasure by pelting him with etrogim (citrons).[18] They made the situation worse by insulting him. They called him a descendant of a captive woman and unsuitable to hold office and to sacrifice. Outraged, he killed six thousand people. Alexander also had wooden barriers built around the altar and the temple preventing people from going near him. Only the priests were permitted to enter.[19] This incident during the Feast of Tabernacles was a major factor leading up to the Judean Civil War.[18]

War with Demetrius III and conclusion of the Civil War

[edit]

After Jannaeus succeeded early in the war, the rebels asked for Seleucid assistance. Judean insurgents joined forces with Demetrius III Eucaerus to fight against Jannaeus. Alexander had gathered six thousand two hundred mercenaries and twenty thousand Jews for battle. Demetrius had forty thousand soldiers and three thousand horses. There were attempts from both sides to persuade each other to abandon positions, but were unsuccessful. The Seleucid forces defeated Jannaeus at Shechem, and all of Alexander's mercenaries were killed in battle.[20]

This defeat forced Alexander to take refuge in the mountains. In sympathy towards Jannaeus, six thousand Judean rebels ultimately returned to him. In fear of this news, Demetrius withdrew. War between Jannaeus and the rebels who returned to him continued. They fought until Alexander achieved victory. Most of the rebels died in battle, while the remaining rebels fled to the city of Bethoma until they were defeated.[20]

Jannaeus had brought the surviving rebels back to Jerusalem where he had eight hundred Jews, primarily Pharisees, crucified. Before their deaths, Alexander had the rebels' wives and children executed before their eyes as Jannaeus ate with his concubines. Alexander later returned the land he had seized in Moab and Galaaditis from the Nabataeans in order to have them end their support for the Jewish rebels. The remaining rebels who numbered eight thousand, fled by night in fear of Alexander. Afterward, all rebel hostility ceased and Alexander's reign continued undisturbed.[20]

Final campaigns

[edit]From 83 to 80 BCE, Alexander continued campaigning in the east. The Nabataean king Aretas III managed to defeat Alexander in battle. However, Alexander continued expanding the Hasmonean kingdom into Transjordan. In Gaulanitis, he captured the cities of Golan, Seleucia, and Gamala. In Galaaditis, the cities of Pella, Dium, and Gerasa. Alexander had Pella destroyed because its inhabitants refused to Judaize.[21]

He is believed to have expanded and fortified the Hasmonean palace near Jericho.[22]

Death

[edit]

For the last three years of his life, Alexander Jannaeus suffered from the combined effects of alcoholism and quartan ague (malaria).[21]

After a reign of 27 years, he died c. 76 BCE at the age of forty-nine, during the siege of Ragaba.[23]

In Josephus's "Antiquities," he presents an account that differs from his earlier "War" and Syncellus's accounts. According to Josephus, Jannaeus fell fatally ill on the battlefield at Ragaba, with his wife Salome Alexandra present. Jannaeus instructed her to hide his death until she captured Ragaba and to subsequently share power with the Pharisees. He also requested that she allow the Pharisees to abuse his corpse, believing they would then give him an honorable burial, despite this request violating Deuteronomy 21:22-23. This request is interpreted as Jannaeus seeking atonement for previously violating this commandment by abusing the bodies of crucified Pharisees.[24] Kenneth Atkinson writes that Josephus's style and wording suggest Jannaeus died in Jerusalem and never reached Ragaba. Josephus may have concealed this fact to hide the undignified nature of this death.[24]

Alexander's reign ended with a significant political decision, naming his wife as successor and granting her the authority to appoint the next high priest.[24]

References

[edit]- ^ DGRBM, "Alexander Jannaeus"; RE, "Alexandros 24"

- ^ Corpus Inscriptioum Iudaeae/Palaestinae vol. 3, De Gruyter, p. 53

- ^ Saldarini 2001, p. 89.

- ^ Atkinson 2016, p. 100.

- ^ Gelb 2010, p. 177.

- ^ "ALEXANDER JANNÆUS (Jonathan) - JewishEncyclopedia.com". jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ a b Atkinson 2012, pp. 130 & 131.

- ^ a b Atkinson 2012, pp. 131 & 132.

- ^ a b Atkinson 2012, pp. 132 & 133.

- ^ Atkinson 2012, pp. 133 & 134.

- ^ Atkinson 2012, p. 134.

- ^ Atkinson 2012, p. 135.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Obbink & Holland 2004, pp. 361 & 362.

- ^ Schäfer 2003, pp. 74 & 75.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Obbink & Holland 2004, p. 362.

- ^ a b Atkinson 2012, p. 136.

- ^ Eshel 2008, pp. 117 & 118.

- ^ a b Kaiser 1998, p. 482.

- ^ Eshel 2008, pp. 118.

- ^ a b c Whiston 1895, p. 332.

- ^ a b Whiston 1895, p. 333.

- ^ Eshel 2008, p. 75.

- ^ Whiston 1895, p. 334.

- ^ a b c Atkinson 2016, pp. 132–133.

Bibliography

[edit]- Atkinson, Kenneth (2012). Queen Salome: Jerusalem's Warrior Monarch of the First Century B.C.E. McFarland. ISBN 9780786490738.

- Atkinson, Kenneth (2016). A History of the Hasmonean State: Josephus and Beyond. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9780567669032.

- Eshel, Hanan (2008). The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Hasmonean State. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802862853.

- Fitzgerald, John Thomas; Obbink, Dirk D.; Holland, Glenn Stanfield (2004). Philodemus and the New Testament World. BRILL. ISBN 9789004114609.

- Gelb, Norman (2010). Kings of the Jews: The Origins of the Jewish Nation. Jewish Publication Society. ISBN 9780827609136.

- Kaiser, Walter C. (1998). History of Israel. B&H Publishing Group. ISBN 9780805431223.

- Saldarini, Anthony J. (2001). Pharisees, Scribes and Sadducees in Palestinian Society: A Sociological Approach. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802843586.

- Schäfer, Peter (2003). The History of the Jews in the Greco-Roman World: The Jews of Palestine from Alexander the Great to the Arab Conquest (2nd Revised ed.). Routledge. ISBN 9781134403165.

- Whiston, William, ed. (1895). The Complete Works of Flavius-Josephus the Celebrated Jewish Historian. Philadelphia: John E. Potter & Company.